The Rundown

2023, the year that will be remembered for waiting for the economic shoe to drop, has ended. The big “R” didn’t come to fruition. We’ll soon know if the soft landing is a reality. However, 12 months of interest rate hikes, inflation fighting, and budget cutting impacted venture investments, with Q4 of 2023 taking it on the chin.

In the Q4 DataTribe Insights, we examine the promising areas of cyber investment as security continues to move deeper into software development.

1. Deal Volume Down to Lowest Levels in 5 Years/Down Rounds Up

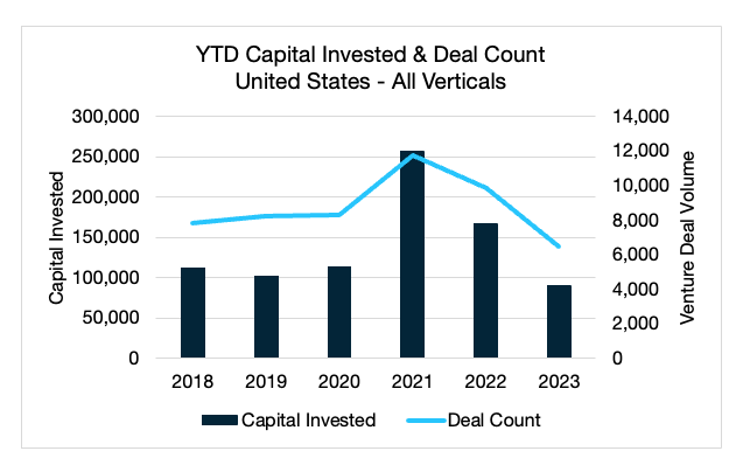

In fiscal year 2023, overall deal volume and capital invested in U.S. private markets continued its decline, totaling $89 billion invested across approximately 6,400 deals. These figures — the lowest in five years — mark a return from the highs of 2021 and 2022. Nearly 20% of companies reported taking money at a lower valuation; a record high 543 closed their doors. This increase in down rounds was felt disproportionately among late-stage startups, with 26.2% of companies taking down rounds for a median decrease in valuation of more than 46%.

2. Secure by Design Takes Shape

In Q4, CISA published an updated version of their secure by design guidance called “Shifting the Balance of Cybersecurity Risk: Principles and Approaches for Secure by Design Software.” This reinforces the unanimity among the world’s leading cybersecurity experts of the nature of the problem. Given the standardized nature of software, it makes sense that global standards will likely emerge.

3. FDA’s SBOM Focus to Make Medical Devices More Healthy

President Biden’s executive order on cybersecurity established the foundation, followed by CISA’s release of comprehensive SBOM (Software Bill of Materials) guidance for IT and OT systems. This momentum culminated in Q4 of 2023, with the FDA issuing dedicated SBOM guidance tailored to medical device manufacturers.

4. Software Supply Chain Security Is Driving Open-Source Innovation

We take a look at some recent developments in open-source tools surrounding software supply chain security and provide a roundup of some useful references.

Introduction

The conflict in the Middle East raged. Inflation continued to wane. Secure by design may finally be ready for primetime. The DataTribe Challenge placed a spotlight on software component security. The venture investment pullback.

Cyber had itself an interesting fourth quarter.

- The economy remained strong, with a 3.3% Q4 GDP overperforming expectations. GDP increased by 2.5% for the year, defying all recession fears and predictions. The unemployment rate remained at 3.7% while wage growth softened.

- Public markets raged, with the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ up more than 14% in Q4. However, M&A activity was down more than 27% compared to Q4 2022. In private markets, the pullback we have seen in previous quarters continued.

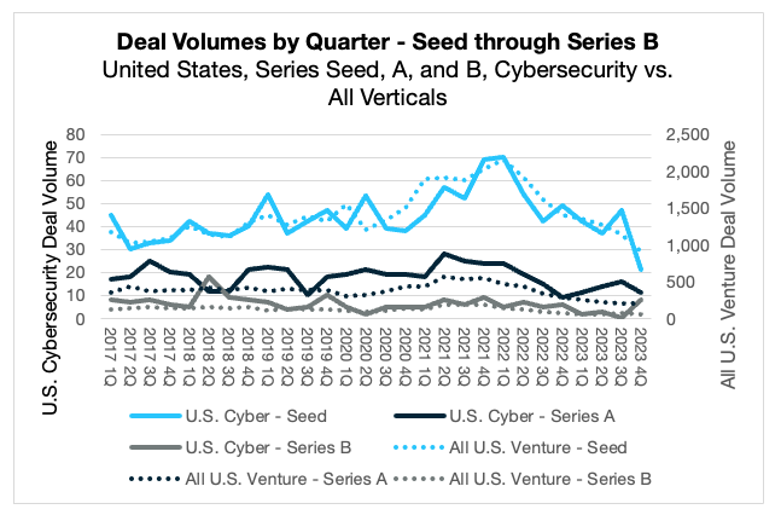

- In Q4, completed deals in the cybersecurity sector decreased 37% from the fourth quarter of 2022. Most of this retreat can be attributed to a decline in seed-round deals, which fell from 49 in Q4 2022 to just 21 this past quarter. While this number of early-stage deals decreased sharply, the amount of capital invested posted a much more modest decline, as decreases in seed capital were offset by an uptick in Series A and B investments.

In this quarter’s installment of DataTribe Insights, we dig into the latest venture market trends, examine the components needed to create a secure software ecosystem, and highlight DataTribe’s investments to help operationalize secure by design practices.

Q4 State of the Market – Cyber Deal Activity

In the fourth quarter of 2023, global markets grappled with renewed conflict in the Middle East, economic uncertainty in China, and the Federal Reserve’s continuation of high interest rates. These challenges have been felt throughout the investment ecosystem, culminating in a slowdown in investment and a continued flight to quality on the part of venture capital funds.

In fiscal year 2023, overall deal volume and capital invested in U.S. private markets continued its decline, totaling $89 billion invested across approximately 6,400 deals. These figures — the lowest in five years — mark a return from the highs of 2021 and 2022. This year has also seen a substantial rise in down rounds and shutdowns. According to data from Carta, among companies using their platform, nearly 20% reported taking money at a lower valuation, and a record high 543 closed their doors. This increase in down rounds was felt disproportionately among late-stage startups, with 26.2% of companies taking down rounds for a median decrease in valuation of more than 46%. This pullback by investors signals a much more competitive market for startups seeking funding than seen in the past five years.

In Q4, the number of completed cybersecurity deals mirrored the broader market pullback, decreasing 37% from the fourth quarter of 2022. Most of this retreat can be attributed to a decline in seed-round deals, which fell from 49 in Q4 2022 to just 21 this past quarter. While this number of early-stage deals decreased sharply, the amount of capital invested posted a much more modest decline, as decreases in seed capital were offset by an uptick in Series A and B investments.

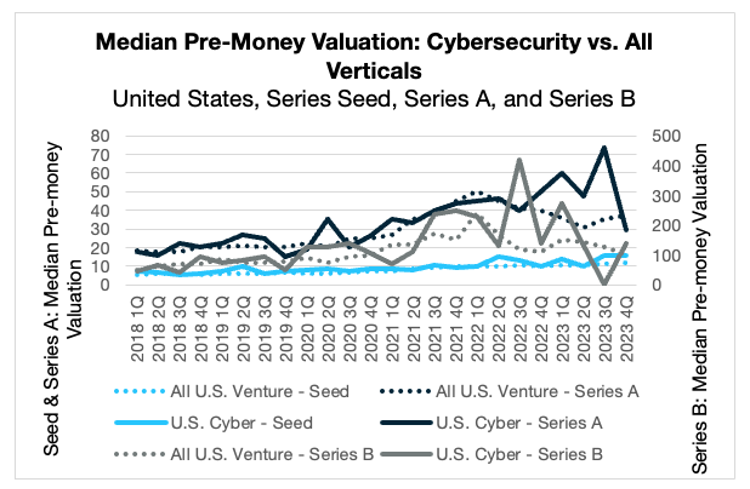

Median pre-money valuations in the seed stage continued their quarter-over-quarter increase, reaching $16 million. These valuations ranged from $1.5 million to $38 million, with many of the higher-valued companies using artificial intelligence in their products — a continuation of a trend from the previous quarter. In Series A, median pre-money valuations declined sharply quarter-over-quarter, from their five-year high of $73.45 million to $29.5 million. When paired with a decrease in volume, this steep decline in median valuation is further evidence of the increased power that venture capital firms hold in the current market.

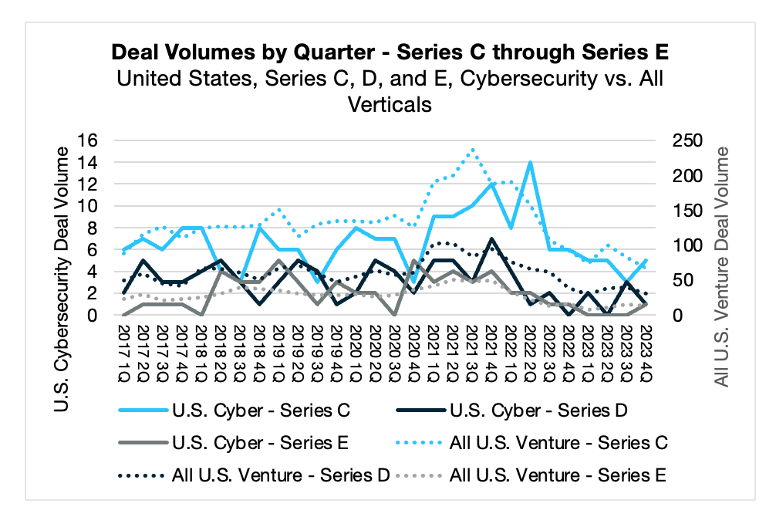

Late-stage growth capital (Series C and beyond) continued to decline in Q4, with the broader market dipping below pre-pandemic levels. The cybersecurity sector saw a slight year-on-year decrease in Series C deal volume from 6 to 5, as well as the first Series E deal of 2023 – likely a symptom of an IPO backlog that is, according to Goldman Sachs, “as high as its ever been.”

Despite venture capitalists having record levels of dry powder, Q4 saw a continuation of downward trends in deal volume and capital invested. This is particularly true in the seed stage, where investors shifted focus to their existing portfolio amid concerns of oversaturated Series A and B markets. This increasing demand-to-supply ratio for capital and upward trend in down rounds suggests that the market will remain investor-friendly entering FY24, and we are optimistic that the cybersecurity sector is well poised for truly differentiated opportunities to stand out.

Just Build More Secure Software in the First Place

In Q4, CISA published an updated version of their secure by design guidance called “Shifting the Balance of Cybersecurity Risk: Principles and Approaches for Secure by Design Software.”

If you haven’t had a chance to read it, the document is an excellent resource. Weighing in at 36 pages, Shifting the Balance of Cybersecurity Risk provides a great primer on how software teams should be re-orienting to ship more secure products in the first place. This version of the guidance, published at the end of October, expands on the initial version, published in April 2023, by adding specific tactics for taking action on the guidance. Here’s a quick snapshot of what’s covered:

- An introductory overview scoping the problem

- Specific recommendations for software manufacturers

- The core principles of secure by design and secure by default

- Tactics for how to take action in advancing the secure by design and secure by default principles

- Recommendations for customers in driving for higher standards of security from vendors

This document aligned with a megatrend that will play out throughout tech for the next ten or more years. We are at the very beginning of a fundamental change in how we build software, a change in the order of the shift from waterfall to agile or when UX was formalized as a key component of product development. As the document states, “Secure by design development requires strategic investment and dedicated resources by software manufacturers at each layer of the product design and development process and cannot be a ‘bolt-on’ later.” While incorporating AppSec, secure by design goes further than AppSec in seeking not just to shift left but to bake security into every step of the product design, development, release, and maintenance. 2023 was an active year for DataTribe in this area. We made two investments in incredible companies (https://www.fianu.io and https://www.vigilant-ops.com) each focused on different aspects of integrating security through the SLDC. We hope that on the other side of this megatrend, the world will have fundamentally more secure products, and customers will not need to be continuously playing wack-a-mole to keep everything from their laptops to their cars patched.

As for the specifics of the guidance CISA outlines, we have a few observations. First, we like it. It’s a great resource for product teams and software developers to guide their journey toward a more secure software development lifecycle. One thing that struck us was the number of cybersecurity organizations worldwide that collaborated to author it, 18 in all. This reinforces the unanimity among the world’s leading cybersecurity experts of the nature of the problem. Given the standardized nature of software, it makes sense that global standards will likely emerge. Overall, we like how the guidance promotes the “secure by” phrase to simplify discussions around this topic: secure by design by default. They added a new “secure by” that we hadn’t seen before, “secure by demand,” which encourages customers to ask tough questions about secure development processes in evaluating products, thus driving market demand. While discussing language choice, we note the term “software manufacturer” throughout the document, which is interesting compared to vendor or software producer. We’re unsure when “manufacturer” was first used for software products. However, as a metaphor much more than a word such as “author” or “publisher,” it does an excellent job of conjuring an image of a fluorescent-lit automotive assembly line with all its complexity, multi-component building, and intricate quality assurance processes involved with software. That said, we say “manufacture” is a bit aspirational. Most organizations, even big ones, don’t yet have software factories, and many software teams operate in small groups that are somewhere between a jazz band and a knitting club.

Overall, the best practices outlined in the document make sense. Though there is a discussion of UX, we propose that the topic of UX as it pertains to security is somewhat buried under the heading “Conduct Field Tests” in the secure by default section. UX is a crucial element of product success. At the center of many security decisions discussed in the product is a UX question of user friction versus safety.

The suggestions outlined in the document are framed heavily in the context of software development versus the more holistic process of product development. We’d propose that readers would benefit from discussing some of the organizational touch points involved in many recommendations, such as marketing, product management, and quality assurance.

We believe that the culture surrounding software development will be a fundamental driver of embedding better security into the product from the start. It needs to become just as professionally embarrassing for vulnerabilities to appear in products as if the product had poor performance. Principle Three, “Lead from the Top,” discusses culture as it pertains to the whole organization. We’d propose that CISA could deepen the discussion of raising awareness and elevating professional norms among software engineers specifically.

In 2023, approximately 28,000 new CVEs (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) were registered in the MITRE-maintained CVE database, up about 15% from 2022. Basically, 28,000 bugs! That’s roughly 80 per day. Could you imagine if cars or refrigerators had that kind of product quality? These numbers scream the desperate need for the secure by design movement. We applaud CISA’s efforts in this area. In fact, we’d go as far as saying there are so many vulnerabilities that even adversaries would wish there were fewer to choose from.

Note: CISA is requesting comments on the document from the community. Further information on how to provide them feedback is here: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/12/20/2023-27948/request-for-information-on-shifting-the-balance-of-cybersecurity-risk-principles-and-approaches-for. The comment period ends on February 20, 2024.

FDA’s SBOM Surge: Strengthening Medical Device Cybersecurity

The cybersecurity landscape for medical devices has undergone a seismic shift in recent months, driven by a concerted effort from the US government and regulatory bodies. President Biden’s executive order on cybersecurity established the foundation, followed by CISA’s release of comprehensive SBOM (Software Bill of Materials) guidance for IT and OT systems. This momentum culminated in Q4 of 2023, with the FDA issuing dedicated SBOM guidance tailored to medical device manufacturers.

While CISA’s focus is broader, encompassing the security of all software and emphasizing supply chain risk and vulnerability management, the FDA’s guidance takes a laser-focused approach. Recognizing the unique risks and complexities inherent in medical devices, it surpasses the “minimum elements” of a standard SBOM by incorporating critical details like known vulnerabilities, support status, and end-of-life dates. This stringent approach prioritizes patient safety and public health, ensuring the absolute security and reliability of every software component within a medical device.

The impact on the medical device industry is undeniable. While increased compliance burdens are unavoidable, demanding adaptation to stricter SBOM requirements, this challenge is eclipsed by the potential for enhanced transparency and risk management. A granular understanding of device software components, facilitated by detailed SBOMs, empowers manufacturers to conduct more thorough risk assessments and implement proactive vulnerability mitigation strategies. While incomplete or inaccurate SBOMs may cause delays in product approvals, the long-term gain outweighs these short-term inconveniences. A robust ecosystem of secure medical devices, protected by rigorous SBOM practices, will ultimately safeguard patient well-being and build public trust in the medical technology sector.

Looking ahead, we anticipate a surge in demand for specialized SBOM management solutions within the medical device industry. Manufacturers must invest in tools and processes that enable efficient generation, management, and reporting of accurate SBOMs to the FDA. This shift will ensure regulatory compliance and drive a paradigm shift towards more secure software supply chains, ultimately strengthening the cybersecurity posture of the entire medical device landscape.

The recent influx of SBOM legislation marks a pivotal turning point for medical device cybersecurity. While navigating the complexities of stricter regulations may present challenges, the ultimate reward is a safer healthcare environment where patients can receive treatment with absolute confidence in the technology entrusted with their lives. The SBOM surge is upon us, and its impact promises to be profound, transformative, and, most importantly, life-saving.

TACOS, SLSA & GUAC – Protecting the Software Supply Chain Can Make You Hungry

Today’s software systems have a complex web of dependencies. They are made of many glued-together software libraries — many open-source, some paid — all running on server software, containers, operating systems, and infrastructure that are also built by gluing together many open-source libraries. This results in even the simplest software depending on thousands of libraries. The Linux Foundation has estimated that today’s modern software systems are comprised of 70%-90% free and open-source software.

Given software’s importance in nearly all aspects of daily life, the complexity of ingredients that make up software creates a massive attack surface that represents a significant risk to the operation of society. In 2023, the trend of scary, high-profile software supply chain attacks continued, with high profile examples such as the PyTorch, Log4J, and SolarWinds attacks. In fact, according to Sonatype’s 9th Annual State of the Software Supply Chain Report, the number of malicious packages found just in open-source software in 2023 was double the number in 2022, coming in at a staggering 245,000.

The seriousness of the problem has prompted significant innovation in the software development community. To help track the complex list of ingredients and the continual discovery of new vulnerabilities and exploits, standards for tracking a Software Bill of Materials, or SBOM, have been developed — including CycloneDX and SPDX. In addition to tracking ingredients, software manufacturing processes must be hardened against attacks and incorporate best practices that can catch malicious or accidental activities leading to software weaknesses. Today, software development teams typically run a somewhat automated process of continuous integration of software pieces and continuous deployment of software versions, commonly called the CI/CD pipeline. Innovative projects such as the SLSA framework and TACOS, both for communicating process maturity, and the in-toto project, which defines a standard for packaging and managing formal attestations, all address securing the CI/CD pipeline and resulting packaged software. Some projects try to combine the SBOM ingredient info and the process and attestation info for a complete picture of software health. GUAC is one such project that was spun out of Google as an open-source project and now has companies building on top of it, such as Kusari who recently announced their seed round of funding.